Vulvodynia (Vulvar Dysesthesia) and Intoital Dyspareunia

- Vulvodynia is defined as chronic vulvar discomfort of 3 months duration or longer, without any clear identifiable cause, but which may have potential associated factors. The pain is often described as burning, stinging, itching, throbbing, stabbing, or rawness. These symptoms, which can be either continuous or intermittent often interfere with the ability of women to have vaginal intercourse, Introital Dyspareunia, wear tight clothing, exercise, or even sit down.

- Vulvodynia affects roughly 16% of the female population. Approximately 5% of all women will experience this condition before age 25. Although all ethnic groups can be affected, it seems to be most prevalent among Hispanics.

- Potential associated conditions include: genetic predisposition, combined birth control pills intake, Interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic muscle over-activity, pelvic organ prolapse, fibromyalgia, myofascial dysfunctions (Orofacial pain), anxiety, depression, childhood victimization, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Patients with vulvodynia undergo a thorough examination to rule out associated visceral or gynecologic conditions. Treatment is tailored individually to the patient's presenting signs and symptoms. It may include Platelet Rich Plasma Rx, anti-inflammatory therapy, diet modifications, anti-depressants, anti-allergenic therapy, physiotherapy, biofeedback, and surgery.

- Dyspareunia is defined as, painful vaginal intercourse of greater than six months duration. Some women have always had pain with vaginal penetration (Primary Dyspareunia), while the majority experience pain at some later date (Secondary Dyspareunia). Pain during vaginal intercourse which is elicited by the initial superficial penetration is referred to as Introital Dyspareunia.

Vestibulodynia (Vulvar Vestibulitis Syndrome)

Definition

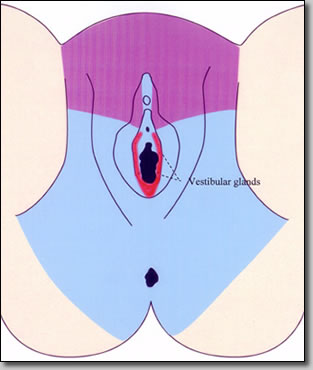

VVS is a chronic (>6 months) inflammation of the vestibular glands, located at the entrance of the vagina (the vestibule). It is characterized by erythema (redness) and severe pain elicited only by touch. The main presenting symptoms of patients with VVS is dyspareunia (painful vaginal intercourse) and terminal dysuria (vulvar burning caused by urination).

Incidence

It is reported that up to 15% of women in private gynecologic practices suffer from VVS. It can affect women of all ages, but is most common in the 18-45 years age group. Afflicted patients are often misdiagnosed, have had the symptoms for many years, and have seen several doctors before their condition is properly diagnosed.

Etiology

1. Anatomical variations: Women with a narrow vaginal introitus and short perineums (space between vagina and rectum) are more liable to suffer from tearing and scarring of the vestibule during sex. The vestibular glands are subjected to intense friction, often resulting in subsequent inflammation.

2. The Human Papilloma Virus (HPV): HPV (the same virus that causes genital warts and cervical dysplasia) has also been shown to be associated with VVS. Patients documented to have this condition, may benefit from interferon (antiviral) therapy.

3. Recurrent vaginitis: Patients with recurrent candidal vaginitis (yeast infection) or cytolytic vaginitis (due to an overgrowth of lactobacilli) may be at an increased risk of developing VVS.

4. Chemical or surgical trauma: Extensive laser vaporization of the vulva or the local application of such chemicals as acetic acid, podophyllin, podofilox, or imiquimod (commonly used for genital warts) can initiate the inflammation of the vestibular glands. The same may occur after surgical trauma, e.g. episiotomy.

5. Allergens / Irritants: A large percentage of patients with VVS suffers also from seasonal and food allergies, pointing to the possibility that allergens may play a role in this ailment. Women using scented tampons, soaps, or detergents, as well as non-cotton underwear, are thought to be at a higher risk for developing VVS.

6. Oxalates in urine: A high concentration of oxalate crystals in the urine, has been shown in one study to possibly exacerbate VVS. Placing these patients on a low oxalate diet, coupled with the intake of calcium citrate tablets (which bind the oxalate crystals) may help.

Associated Conditions

A number of conditions are associated with VVS. Some can be present simultaneously, while others can precede or follow it.

1. Cervicitis: Inflammation or infection of the cervix often results in leukorrhea (discharge) that can further irritate the vestibular glands and result in further worsening of the condition. Treatment of these patients with antibiotics or cryotherapy is usually helpful.

2. Vulvitis: Not uncommonly, VVS presents itself as part of a generalyzed inflammation of the vulva (vulvitis). Although the acute onset vulvitis usually responds readily to therapy, the inflammation of the vestibular glands may persist.

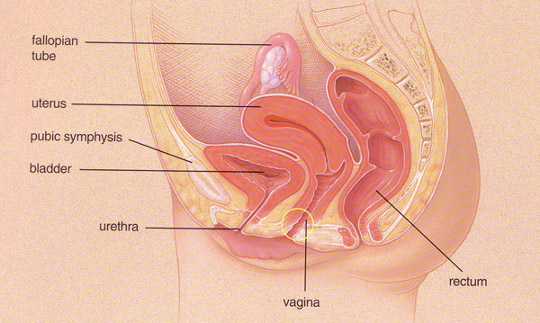

3. Interstitial cystitis: Almost one out of four interstitial cystitis patients suffers concurrently from VVS. This is not surprising, considering the fact that both the bladder and the vulva are derived from the same embryonic cells (endoderm).

4. Vaginismus: Most patients with long lasting dyspareunia secondary to VVS, develop vaginismus (involuntary painful contraction of the vaginal muscles upon penetration of the vagina). After the VVS has been successfully treated (either medically or surgically), the patient has to be helped to overcome her vaginismus with the use of dilators and vaginal relaxation exercises.

5. Emotional stress / Marital disharmony: The severe dyspareunia that always accompanies VVS, prevents loving couples from having sexual intercourse. When this condition persists for years, it often results in some degree of stress, depression, and marital disharmony. Psychosexual therapy is often helpful in providing guidance and support during this period of crisis.

6. Vulvar cancer: Vulvar biopsies obtained from patients with chronic vulvar irritation, occasionally reveal vulvar cancer (Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia). The incidence is higher among patients infected with the HPV.

Vaginismus

Vaginismus is defined as the recurrent or persistent involuntary contraction of the perineal muscles surrounding the outer third of the vagina -see diagram-, when vaginal penetration with penis, finger, tampon, or speculum is attempted. In some females, even the anticipation of vaginal insertion may result in muscle spasm. The contraction may range from mild, inducing some tightness and discomfort, to severe, preventing penetration and coitus (introital dyspareunia).

Sexual responses (e.g., desire, pleasure, orgasmic capacity) may not be impaired unless penetration is attempted or anticipated.

The disorder is more often found in younger than in older females, in females with negative attitudes toward sex, and in females who have a history of chronic vulvar pain (vulvodynia), or sexual abuse.

Lifelong or primary Vaginismus usually has an abrupt onset, first manifests during initial attempts at sexual penetration by a partner or during the first gynecological examination. Once the disorder is established, the course is usually chronic unless ameliorated by treatment. Acquired or secondary Vaginismus also may occur suddenly in response to a sexual trauma or a general medical condition, e.g. vulvar vestibulitis syndrome.

Since Vaginismus may remain as a residual problem after resolution of the associated medical condition, the therapy of vaginismus is an integral part of the medical care for vulvodynia. It consists of desensitization exercises, that include Kegel exercises, vaginal relaxation and physiotherapy, as well as gradual dilator therapy.

Vulvar Neuropathy

Vulvar neuropathy is defined as chronic vulvar pain in the absence of evident pathology on pelvic examination. It can sometimes be secondary to painful sensory diabetic neuropathy, which may be unilateral or bilateral in its distribution. It may present as an isolated symptom or as a part of constellation of other neuropathic abnormalities, or post herpetic neuralgia (after Shingles).

A. Nociceptive pain

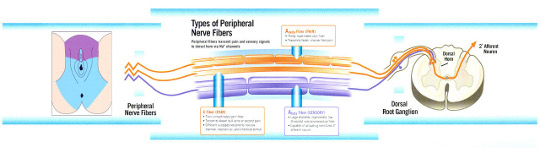

Normal pain perception (Nociceptive pain) results from stimulation of intact peripheral nerve fibers (pain sensors) in the vulva. Mechanical (trauma), thermal (heat or cold), or chemical (caustic substances) stimulation of the vulva, gives a good and normal information and warning to the brain, that the vulvo-vaginal area is damaged or about to be damaged.

B. Types of peripheral nerve fibers

There are three types of fibers that carry pain signals from the vulva to the brain: A-beta, A-delta and C-fibers. The first two are well evolved, myelinated (insulated) fibers that rapidly carry, well defined sharp, lancinating pain signals to the cortical (upper) regions of the brain. The C-fibers are relatively primitive, unmyelinated fibers that slowly conduct ill defined aching and burning sensations to the subcortical region of the brain.

| CHARACTERISTICS OF PERIPHERAL NERVE FIBER TYPES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Stimuli/function | Perception | Velocity: m/sec | Diameter: micron | Myelination |

| A-alpha fibers | Motor contraction Efferent transmission | None | 30-85 | 12-22 | + + + |

| A-beta fibers | Vibration and pressure Afferent transmission | Vibration and pressure | 30-70 | 5-12 | + + + |

| A-delta fibers |

Cold sensation and pain |

Cold sensation and pain |

5-25 | 1-4 | + + |

| C fibers | Hot sensation and pain Slow pain and generalized touch Afferent transmission | Hot sensation and pain generalized touch |

0.7-2.0 | 0.3-1.3 | - |

C. Neuropathic pain

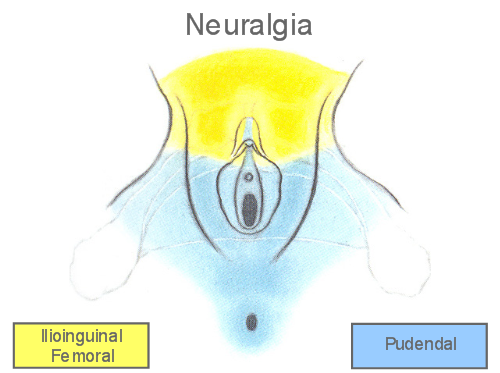

The pudendal, genitofemoral, and ilioinguinal nerves are the main nerves serving the vulvo-vaginal area. Any trauma or damage to the vulvo-vaginal area can traumatize the nerves themselves. Damage to the neural transmission can manifest itself analogous to “static” in radio transmissions. This neural “static” results in the spontaneous firing by the C-fibers of the vulva, and is perceived as a continuous dull, aching, or burning pain. Neuropathic pain results therefore, from damaged and malfunctioning nerve fibers.

D. Therapy of neuropathic vulvo-vaginal pain

Neuropathic vulvo-vaginal pain can be successfully treated with Gabapentin (Neurontin) an anti-convulsant, 300-1200 mg PO tid, or Amitriptyline (Elavil) a tricyclic anti-depressant, 0.5-2 mg/kg PO qhs. Both of these drugs seem to help reduce the “static” spontaneous firing of the C-fibers. If the pudendal neuralgia is associated with levator ani myalgia, a bilateral pudendal block will help relieve the painful spasm.

Vulvar Dermatoses (Vulvar Dystrophy, Lichen Sclerosus)

Vulvar Dermatoses (old nomenclature: vulvar dystrophies) constitute the most prevalent entity of vulvar diseases.

They comprise four groups:

- A. Lichen planus

- B. Lichen simplex chronicus (Neurodermatitis)

- C. Lichen sclerosus

- D. Mixed dystrophy

Common Characteristics:

Vulvar dermatoses share some common characteristics: They are all benign, idiopathic, pruritic, & affect multiple body sites. Although, they can occur in younger females, they are most commonly found in post-menopausal women. Diagnosis is usually confirmed by vulvar biopsy, & although no cure is available, supportive steroid therapy is often successful in alleviating the symptoms.

A. Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is an uncommon eruption of small papules that can involve the wrists, ankles, groin, genitalia, & oral mucosa. On the vulva the disease often manifests itself as annular erosive lesions with clear margins. The condition often lasts between 6 months to 2 years.

B. Lichen Simplus Chronicus

Persistent unexplained itching and rash characterize lichen simplus chronicus also referred to as neurodermatitis, eczema or hyperplastic dystrophy. The itching is usually intense, and the rash often involves the perineum of both sexes, the side of the neck in women, and the ankles in men. Large patches of thickened, scaly, and occasionally hyperpigmented skin (lichenification) is commonly found. Foci of atypical changes or cancer may lie within these areas. Symptoms often develop or worsen during stress, but once a lesion resolves, recurrence is uncommon.

C. Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is a common disease of the vulva that can occur at any age, but is most common in post-menopausal women. The neck, trunk, and extremities can also be involved. The disease causes a gradual fusion of the labia and prepuce of the clitoris. The thinned-out skin becomes pale and wrinkled like a parchment. Foci of atypical tissue or cancer should always be sought at the time of initial evaluation. These changes are symmetric and recurrence is common. Pernicious anemia, achlorhydria, and autoimmune disorders have occasionally been associated with lichen sclerosus.

D. Mixed Dystrophy

Occasionally patients present with mixed vulvar changes of lichen sclerosus and hyperplastic dystrophy: Areas of thinned and thickened skin lie next to each other. Multiple biopsies are important since mixed dystrophies have a slightly higher incidence of atypia.

Non-Sexually Acquired Genital Ulcers (NSGU)

- NSGU are aphtous genital ulcers, probably secondary to a compromised immune response, which often occur in association with oral aphtous ulcers. They may be very painful and result in dysuria (pain with urination) or prevent urination altogether (acute retention of urine) requiring admission to the hospital and catheterization. Local lymph nodes may be enlarged and tender.

- They are subdivided into 2 types:

- Reactive genital ulcers: generally occur following an acute systemic illness such as tonsillitis, upper respiratory tract infections or diarrheal disease. They mainly affect adolescent girls but may sometimes arise in adult women. They usually resolve within a few weeks and rarely recur.

- Recurrent genital ulcers: the ulcers tend to be smaller than reactive genital ulcers and may recur regularly, (e.g., prior to menstruation) or infrequently. They also can be seasonal. Behçet disease and Crohn's disease have to be ruled out.

- The traditional treatment of NSGU is usually a combination topical anesthetic, corticosteroid, and soothing ointments. Oral steroids and antibiotics are occasionally used. PRP therapy could probably be very helpful.

Vulvar Adhesions in Prepubertal Girls

- Labial adhesions can occur in prepubertal girls from the age of two months to 11 years. It can be successfully treated with the application of topical estrogen therapy alone or in combination with manual separation of the labia.

- Several weeks of therapy are needed depending on the degree of adhesions. Maintenance therapy with a topical emollient is needed in recurrent cases (6%).

Pudendal Neuralgia and Pelvic Floor Hypertonic Dysfunction/ Overactivity (Levator and Myalgia)

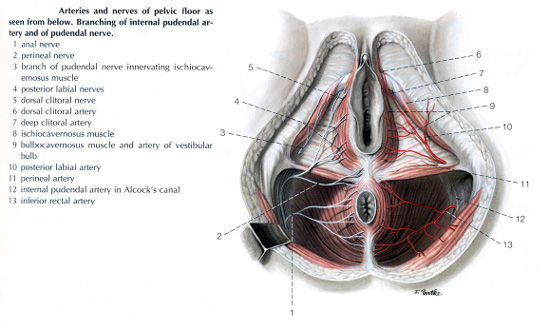

The pudendal nerve is the main nerve supply of the perineum. The nerve divides into several branches including the inferior rectal nerve, the perineal nerve, and the dorsal nerve of the clitoris. Irritation of the nerve (pudendal neuralgia) often results from trauma secondary to childbirth or bicycling, and can result in multiple dysfunctions; these include clitoral, vulvovaginal, and rectal pain and discomfort, introital dyspareunia (painful vaginal penetration during intercourse), and restless genital syndrome.

Painful spasms of the pelvic floor muscles -Levator ani-, is often the presenting symptom of patients with vulvodynia. This condition has been called several names including levator ani syndrome and myofascial dysfunction.

Myalgias of the pelvic floor are often the result of trauma and/or inflammation of the perineal branch of the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve originates from the S2-S4 region of the spinal cord, and serves to transmit both sensory input to the vulva and perineum, as well as motor function to the muscles of the pelvic floor and external sphincters of the urethra and rectum.

Inflammation of the pudendal nerve -Pudendal Neuralgia- could result from a number of factors. These include: stretching or injury during labor, vaginal delivery or episiotomy repair; accidental trauma to the pelvis and vulvar-vaginal procedures or infections. This in turn causes painful spasms of the affected muscles and fascia that become knotted and unable to relax. The surrounding muscles try to compensate, often resulting in "overloading" of the muscles and the development of painful trigger points (fibromyalgia).

Treatment of pelvic muscle myalgias may require pudendal block and/or pelvic physiotherapy and biofeedback.

Clitorodynia and Restless Genital Syndrome (Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder)

- Clitoral pain is characterized by frequent and intense pain episodes that can either be provoked or unprovoked, and causes significant impairment in both daily and sexual function. The pain can be localized to the clitoris only or can occur with other genital pain. Comorbidity with other chronic pain disorders is common.

- Pudendal Neuralgia with irritation of the dorsal nerve of the clitoris, or ilioinguinal/genitofemoral neuralgias have been implicated as probable causes of Clitorodynia. Nerve blocks are therefore helpful for relief of pain.

- Restless genital syndrome (RGS) is defined as persistent unpleasant, spontaneous, intrusive, and unwanted genital arousal characterized by tingling, throbbing, & pulsating sensations that occurs in the absence of sexual interest and desire. Symptoms are worse at night when the patient is lying down. Patients often report an urge to get up and move to alleviate the symptoms.

- Some authors have associated RGS symptoms with pudendal nerve or dorsal nerve of the clitoris neuropathy, Tarlov cysts, or genital vasocongestion, which may justify an investigation for those conditions as a differential diagnosis.

- RGS is quite often associated with restless leg syndrome. The same drugs can be applied in both conditions: Dopamine agonists (eg, pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine) can be very effective.

- This is one of the first-line drug classes for RLS, along with pregabalin, gabapentin, opioids and clonazepam which also has been successfully used. Iron supplementation is recommended in selected patients, mainly in those with low ferritin levels.

Chronic Perineal and Peri-Rectal Tears

- Chronic, recurrent fissures of the perineum & peri-rectal area, are often associated with severe vulvovaginal atrophy (genitourinary syndrome of menopause), vulvar dermatoses, badly healed scars, narrow vaginal introitus, and chronic constipation. This is often accompanied by severe introital dyspareunia.

- PRP therapy is very helpful. The epidermal and connective tissue growth factors in PRP, help expedite the healing process & could help the patient avoid the need to undergo perineoplasty (surgical repair of recurrent perineal tears).

Deep Pelvic Pain and Deep Dyspareunia

Patients with chronic level 3 dyspareunia (deep dyspareunia), usually exhibit pain during deep thrust vaginal intercourse. The tenderness can be reproduced during a pelvic examination, by moving or pressing against the cervix or uterus. The most common causes of chronic deep pelvic pain are: Endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, and pelvic congestion syndrome.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the most common cause of chronic pelvic pain. It is most common in young nulliparous (no pregnancies) women with a family history of the disease.

It is characterized by the growth of endometrium-like implants (endometrium is the tissue lining the uterus) on the pelvic organs &/or bowel. These implants respond to changes in hormones and break down and bleed like the lining of the uterus during the menstrual cycle. This bleeding can cause pain and adhesions (scar tissue). Bleeding into the ovaries may cause the formation of hemorrhagic painful cysts called endometriomas. Etiology is unclear.

The main symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea (pelvic pain just before or during the menstrual cycle) &/or dyspareunia (pain with deep thrust vaginal sex). If the endometriosis lesions are located on the bladder or recto-sigmoid colon, pain may also occur during urination or bowel movements. Endometriosis can be mild, moderate, or severe. Severe cases may be associated with infertility. Although the amount of pain does not always reflect how severe the condition is, recent studies tend to associate the severity of dyspareunia with the severity of the disease.

The diagnosis of endometriosis can be suspected clinically (history of secondary progressive dysmenorrhea &/or deep dyspareunia), or confirmed by laparoscopy.

Endometriosis may be treated with medication, surgery, or both. Although treatments may relieve pain for sometime, signs and symptoms tend to recur.

Medical therapy is geared towards suppressing the estrogen production by the ovaries. Towards that end a number of medications can be used including: Oral contraceptives, progestins, Danazol, & gonadotropin-releasing hormones (GnRH). The length of therapy (usually 6 months) is tailored to the severity of the disease.

Surgical therapy can be conservative or definitive. Conservative surgery consists of resecting or cauterizing the endometriosis implants and adhesions through laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy. Symptoms tend to return within one year in about 50% of women who have had surgery. The more severe the disease, the more likely it is to return. In severe, recurrent cases, hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of uterus, cervix, tubes & ovaries) may be required.

Pelvic adhesive disease

Adhesions or scar tissue can form as a result of inflammation or healing. Endometriosis, surgery, or a severe infection such as pelvic inflammatory disease, or a ruptured appendix can cause adhesions. Scar tissue causes the surface of organs inside the pelvis to bind to each other. Adhesions can involve the uterus, tubes, ovaries, bladder, or bowels. They can attach any of these structures to each other or to the side walls of the pelvic space. This rigidity or fixation of the pelvic organs can result in chronic deep pelvic pain, and often would cause severe tenderness during vaginal intercourse (deep dyspareunia).

Diagnosis is usually made by laparoscopy.

Resection of the adhesions can often be performed, as an outpatient, through the laparoscope. In cases of severe pelvic adhesive disease, releasing the adhesions through an exploratory laparotomy or even a hysterectomy may be required.

Pelvic congestion syndrome

Pelvic congestion syndrome is a condition of chronic pelvic pain associated with the presence of pelvic varicosities. The pain may be of variable intensity and duration, is usually worse premenstrually and during pregnancy, and is aggravated by standing, fatigue, and coitus. The pain is dull and often described as a pelvic "fullness" or "heaviness." It may extend to the vulva-vaginal area and legs.

The signs and symptoms of the Pelvic congestion syndrome occur after pregnancy and do not persist past menopause, suggesting a strong correlation between hyperestrogenic states and pelvic congestion. This concept is supported by a report of improvement in pain following pharmacologic ovarian suppression.

Diagnosis can be made by laparoscopy which would reveal multiple ovarian and/or pelvic varices or by radiology (CT scan, MRI, or venography) which confirms dilation of the ovarian and pelvic veins and the presence of passive reflux.

Therapy may range from pharmacologic ovarian suppression (e.g. continuous birth control pills), to interventional radiologic treatment by transcatheter embolization, to total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophrectomy (removal of uterus, cervix, tubes & ovaries).